By Åke Bjørke March 2014

Good online education can be a driving force for quality enhancement, course development procedures, internationalisation of studies and joint degrees between networks of educational institutions. However, there are many problems and challenges. A reliable electricity supply, broadband facilities, appropriate computers and software are obvious stumbling blocks. The pedagogical problems and challenges can be even more daunting. Internationalisation of courses and making people of very heterogeneous ages, backgrounds, educations, cultures and languages collaborate in virtual communities of practice can be a mouthful even to the most experienced lecturer.

Introduction

An online tutor has similar challenges as ordinary teachers, and some in addition. Tasks that can be done more or less unconsciously in a face-to-face classroom must be done consciously and deliberately online. Students, especially from the developing world, may have been exposed to a “colonial style” pedagogy resulting in “lack of confidence and ability in independent study because of their experiences with an authoritarian methodology which promoted rote learning and rewarded dependent behaviour” (Randell and Bitzer, 1998, p.139).

The main role of the tutor is to guide and support the learning process by helping learners to find and assess additional resources, guide interaction with peers and provide support to empower the learners (Higley, 2014). A main learning resource is peers, and tutors must ensure opportunities for interactivity and participation. Learning activities must therefore be designed and conducted in a manner that helps students engage with the subject matter and with fellow students. Peer interaction is crucial online. Without, the dropout rates will be substantial. In addition to have a good grip on the subject in question, tutors need insight and training in order to handle the problems and challenges of the virtual classroom, some of which are described below.

Problem #1. Online students are undisciplined

Even if the students have committed themselves to frequent log-ins; reality can be quite different. You cannot look your students in their eyes and instruct them, you have to communicate in writing. Online students are like most of us; they tend to dislike reading instructions. Study guides are not always read as carefully as needed.

Challenge: make progress at a pace suitable for the majority while avoiding losing those less eager to participate.

Problem #2. You cannot yell at your students

In a face-to-face situation you can use your body language, voice tone, and scream and yell at your students, if you think that helps. If you “YELL” at your students online, they will most likely avoid reading your messages at all.

Challenge: Compensate for the lack of social cues and rich communication present in a face-to-face setting.

Collaboration must be learned. This usually is quickly done during a well-planned face-to-face session at course start-up.

Problem #3. Collaboration online is not intuitive

In a face-to-face situation students can discuss their subject without being conscious of that this is what they are actually doing. “How far have you come in your reading? What do you think of it?” “What did the professor say about this?” etc. This is one of the advantages of on-campus studying: the students can “negotiate meaning” in the campus café, combining it with socialising, making it pleasant. Online, this must be done deliberately and planned. The idea that interaction must be explicitly designed in online courses is difficult for many teachers to accept and understand.

Challenge: make online learning a social and pleasant experience.

Problem #4. Infrequent on-loggers get lost

Participants logging in only once a week or less, are met by a ‘sea of red flags’, indicating many unread messages. They may struggle to follow discussions going on, and the other group members may get annoyed when a group member does not contribute.

Challenge: make students participate and contribute frequently in a good spirit of collaboration.

Problem #5. Students want to be taught

Traditionally, students demand to be taught, perceiving themselves as receivers more than actors. This desire to be taught and passively receive may cause problems for teachers requiring active students taking responsibility for their own learning.

Lectures continue to dominate pedagogical transactions in higher education. A conspiracy has grown up between both teacher and taught to ensure that pedagogical processes are as free as possible of unpredictability, stress, openness and multiple contending voices… (students) are hardly likely actively to seek out pedagogical processes that place more responsibility upon them for their own learning (Barnett and Hallam, 1999, pp.146-147).

Many adult learners grew up in a competitive education model where learners had to outshine one another to attain the highest grades. This in contrast to the mainstream pedagogical approach in e-learning: the socio-cultural pedagogy, demanding active participation and interaction of the students, and where learning is defined as increasing participation (Lave and Wenger, 1991, p.15).

Challenge: move tutors away from the traditional explicative, transmissive and “banking” modes of working over to more facilitative methods and explain this in easily understandable ways.

Problem #6. Lengthy messages in the discussion forum.

It is tedious to read long texts on a screen. Some participants have difficulties in making short and to-the-point “post-card” size messages, and instead write lengthy contributions in the discussion forum. Worse is that too often these lengthy texts are some copy and paste work from unspecified sources. Many students as a result skip reading these long messages, and may therefore lose important points.

Challenge: Convince participants that in an online discussion environment (and elsewhere as well), “less is more”. Short, to the point messages communicate better and have more impact. Lengthy messages belong in the “Archive” function, not in the discussion forum. Messages marginal to the discussion at hand should be placed in “the online café” or similar places to avoid tiring those not especially interested.

Problem #7. Stray files.

Some participants need a long time to get a good grasp of understanding the systems and strict structures of the online classroom. Many stray files placed outside the correct virtual group rooms (folders) make it difficult to navigate and finding the correct ongoing discussion. Some participants spend so much time searching for the right place that they give up their study because they get lost in a jungle of stray files on a slow internet connection.

Challenge: Balancing the need to learn and use the structures correctly for the individual participant against the need for the group to navigate efficiently in the virtual rooms.

Problem#8. The student is supposed to become an independent and self-reliant learner, but shall also rely on others to learn

Constructivist pedagogy strives to develop reflection and the skill of learning how to learn. The goal of facilitating learning is to support the development of independent learning, and eventually guide the learners to teach themselves. In addition, socio-constructivist pedagogy emphasises learning by collaborative activities in a relevant context. “Positive interdependence is the knowledge that you are linked closely with others in the learning task and that success (personal and for the group) depends on each person working together to complete the task” (McConnell, 2000, p.121).

Challenge: develop a good online community of practice in a multicultural and global virtual room.

Problem # 9. Pacing a course by giving time-frames for activities and cut-off dates for hand-ins are often contrary to on-campus traditions as well as traditional distance education.

In collaborative studies, the learning activities must to some extent be synchronised. The participants do not have to be present during the same hours, not even the same day. But they must participate frequently during the activity’s time-frame to be recognized as participants in the community of practice. Most professors are used to plan progression by their own lectures, not by their students’ activities. To the traditional distance education institution, pacing a group progress is contrary to the philosophy of the studying anytime, anywhere and at the student’s own pace.

Challenge: Calculating the correct time needed for the different learning activities; balancing amount of content with the time needed for group discussions and the ‘ECTS hours’ available in the module.

Problem # 10. Distance students tend to feel isolated, and may get de-motivated without the human touch in the technological environment

Some may feel that online learning is dehumanised and alienating, and most self-instructional courses, in spite of interactivity between learner and machine, may over time be perceived as such. Traditional didactic teaching made online may be perceived similarly. In Computer Supported Collaborative Learning (CSCL) voice-tone, facial expression and body language are missing. Collaborative learning depends on openness, warmth and empathy. A challenge for the e-learning environment is therefore to build social presence, which means that a tutor is perceived as a real person who engages in the learner’s needs and progress.

Challenge: develop personal and social presence and build a social environment online. E-learning should be near and personal, not distant.

Problem # 11: The education arena tends to be a secluded place. How do we make data matter? Students have their individual pace of progress. How can a teacher help a heterogeneous group of students to go from information gathering to information literacy to critical thinking to creative contributions?

Socio-constructivist learning involves information literacy: search relevant, valid and reliable information and critically assess it. The next challenge is the critical stage: “can I use this information to solve a problem or apply it in the task at hand?” The student must also accept critical comments from the peers. “Is this piece of information relevant and good enough to be used in our common document or project?” Critical thinking is applied throughout the process. But critical thinking is not enough. Each participant must proceed; go from idea to practice, from critical thinking to creative contribution. Students must learn how to make an argument, give a rationale and a line of reasoning, take a stand or idea and explain why it is logical or not. What are the assumptions and premises behind? Can the student – or the group – come up with constructive criticism? And then follow up with a practical solution to a problem? Active learning and active social change go together. We want the students to be engaged, active, critical, taking initiative, taking responsibility. We want to encourage students to take the lead. Can we train students in leadership? A thesis or a term paper is then probably not enough. The findings should have some social impact, maybe cause some sort of transformation. In transformative pedagogy we want to proceed from the instructivist one correct answer to diversity.

Challenge: move upwards in the Bloom’s hierarchy of knowledge and make the new knowledge count. How do we make pedagogy transformative and make learning go beyond the classroom?

Problem # 12 Assessments. The end of grade test

How can we ensure that we test what we value? The traditional test is summative. A summative test tends to assess how good you are at taking a test, not necessarily how much you actually have learned. Ideally, knowledge and skills should be demonstrated through practical performance, not through a standardized test with multiple choice questions. Students tend to focus on how to pass the end of grade test, and less on learning. How do we make assessments an effective part of learning activities? We know that the formative kind of tests give more room for learning than the summative tests. Formative tests give feedback on how to improve. In other words, formative tests involve constructive criticism, summative just criticism. Some have compared formative tests to regular medical examinations with a check of status and good advice on how to do better. A summative test is comparable to the autopsy. So why do we do all this summative testing? There are other ways of assessing knowledge and skills than just school exams. A standardised test asks all to do the same test, no matter of personal interests and skills. Future learning should perhaps individualise more. Should we for example consider using badges in learning more frequently? Badges indicate skills or accomplishments earned in different kinds of learning environments. Many know this kind of assessment system from boys and girls scouts and the military. But this type of assessment requires a more flexible approach to education than we are used to today.

Challenge: We know quite a lot about what works in learning. How can we apply what we know works well to make a best possible learning environment?

Learning should be active and if possible situated in the context we are learning about. DM students at community micro finance projects in Colombo.

Pedagogical planning of learning as activities

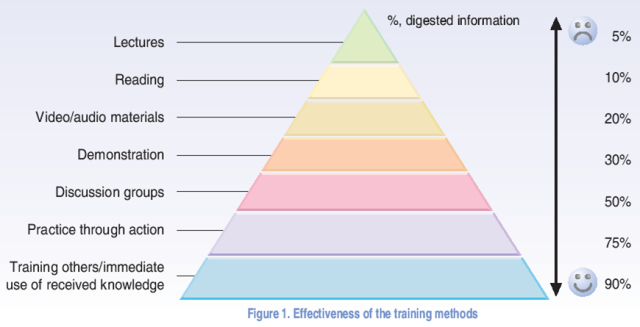

The philosophy is that learning takes place when the learner is active. When the task is to learn e.g. about “the environmental issue of invasive species”, it is considered insufficient just to read about the subject in a book or two. The student must of course read, search for alternative information and try to formulate own opinions. In addition, the student should confront his or her understanding with that of peers in online discussions. The student will thereby read several ways of presenting the issue, and quickly find that there is no “facit”, but that it is necessary critically to build a broader, more multi-faceted understanding in collaboration with others. In this way, much of the information gathering, arguing, thinking and reasoning take place in online discussion fora, where the student must apply the information found in ongoing discussions. This means information is used and thereby learned, according to the lowest and broadest step on the learning pyramid.

The online discussions are intended to rationalise production of concrete results, and thus connected to and act as a basis for the writing of articles and hand-ins, whether this is done by the group or individually. Students who participate actively in the discussions find that their understanding of the issue, their ability to form critical standpoints and their ability to express opinions instead of just repeating a source will be considerably strengthened.

The learning pyramid indicates that learning activities might increase retention better than just a one-way lecture. Source: Veligosh, E. (2004): developing and delivering training on the Aarhus Convention for Civil Society. A manual for trainers. European Commission. ISBN: 966-8026-51-9 (The percentage figures are of course just giving an indication)

Conclusion

New communication technologies can be used to transform staff development, making good learning environments and creating communities of practice in dual-mode or purely online modes. Universities should be good places to learn; face-to-face, online or in combinations, and in addition develop the institutions into good learning organisations. Online learning is not easier on students, but correctly planned and implemented, the learning experience can be at least as good as most on-campus education (Bhaskar, 2013)

Internationalised online education is a specialised field of expertise, and building competence is necessary in the fields of ICT, e-pedagogy, frameworks for international quality assurance, credit accumulation and transfer, cross-cultural communication and understanding.

A full time study programme is ambitious in itself. Asking the students to study mainly online, taking an MSc degree over two years, is challenging. Considering that online studies can be tough enough in Europe, they will be even tougher in Africa south of Sahara. With frequent electricity breakdowns and poor Internet connections, the margins are narrow.

Asking small groups of students associated to the local universities to meet frequently, may be a remedy to some extent. However, there must be no doubt that the tutors’ role is decisive.

To support and motivate the tutors and students, occasional face-to-face sessions can be good vitamin injections. The tutors and professors may also meet physically at least once per semester. Providing tutors as well as course-writing professors and others involved in the online studies with the necessary training and support must always be a main task for the administration of such initiatives. Above all, sufficient time for the task is necessary.

Globalisation processes without doubt challenge the education systems in all countries, not

only in Africa: ”European school systems must learn to be more flexible and effective in improving learning outcomes.”…” if Europe wants to retain its competitive edge at the top of the global value-added chain, the education system must be made more flexible, more effective and more easily accessible to a wider range of people” (Schleicher 2006).

Internationalised online education and collaboration in networks can be important driving

forces for developing modern and flexible education adapted for lifelong learning. A well

functioning network of equal partners facilitates development of high-quality courses and

study programmes ensuring currency, relevance and a broad curriculum catalogue.

There are high expectations to the educational systems everywhere. In order to encourage and enable educational institutions to build knowledge-rich, good learning environments and take responsibility for the learning outcomes, readily accessible and extensive support systems are necessary.

Photos: Å. Bjørke

References

Barnett, R. and Hallam, S. (1999) Teaching for supercomplexity: A pedagogy for higher education, in Mortimore, P. (ed.): Understanding pedagogy and its impact on learning, London, Paul Chapman Publishing.

Bhaskar, S. (2013) Busting Myths About Online Learning, in Easyclass http://edtechreview.in/e-learning/610-busting-myths-about-online-learning

Higley, M. (2014) e-Learning: Challenges and Solutions, in E-learning industry, http://elearningindustry.com/e-learning-challenges-and-solutions (March 2014)

Lave, J. and Wenger, E. (1991) Situated Learning: Legitimate peripheral participation, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

McConnel, D. (2000) Implementing Computer Supported Cooperative Learning, London, Kogan page

Randell, C. and Bitzer, E. (1998) Staff development in support of effective learning in South African distance education, in Latchem, C. and Lockwood, F. (eds.) Staff development in open and flexible learning,London, Routledge.

Schleicher, A. (2006) The economics of knowledge: Why education is key for Europe’s success. The Lisbon Council policy brief. http://www.lisboncouncil.net/publication/publication/46-the-economics-of-knowledge-why-education-is-key-to-europes-success.html

Other sources:

Hakala, C (2015) Why Can’t Students Just Pay Attention? Faculty focus

Very soon this web page will be famous amid all blogging users,

due to it’s nice articles

LikeLike

Homework and tests should be as realistic as possible. How often does a student need help, not with the questions themselves, but with a puzzling system. My son use to had a lot of problems while he is doing his homework, especially with the chemistry. Anyway I found way how to helped him – online chemistry course. If somebody needs any help with any kind of homework these guys here can help you http://www.mrscienceteacher.com/

LikeLike

Thanks for the link. I agree that the percentages in the learning pyramid are highly questionable. To actually believe that those figures can be generalised to all situations is obviously wrong. We all know that some lecturers are fantastic teachers, and that we can learn a lot just by listening. Others are lousy and we learn nothing.

However, as a kind of heuristic, the learning pyramid can be quite useful. If we forget about the percentages, as a rule of thumb, a good lecture will include pictures (mental or real) and maybe demonstrations. We also know that the cognitive processes that ensure retention, most likely will take place when the students are active themselves. Dewey’s old slogan is still valid: learning by doing. Good learning is usually an active process.

LikeLike

An interesting article. Some of it is undermined, unfortunately, by the citing of the discredited “learning pyramid.”

This article:

http://informahealthcare.com/doi/pdf/10.3109/0142159X.2013.800636

deals with the learning pyramid in medical education, but the introduction is a summary explanation of just how bogus it is.

LikeLike